We sit down with Alex McKay and talk wine. Here, Alex talks about his longstanding interest in Italian varieties, why sangiovese is so well-suited to the Canberra region, and the evocative and expressive wines it can make.

The book

My interest in Italian varieties and Italian winemaking methods was really sparked as a student. In 1996, while studying winemaking at the University of Adelaide, I was fortunate enough to receive a Summer Studentship with the Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture. The project I undertook had been conceived by Garry Crittenden, a pioneer of Italian grape varieties in Australia. He was looking for some hard data and I guess a scientific basis to the work he was doing to introduce these varietals to the industry and wine-lovers alike.

My interest in Italian varieties and Italian winemaking methods was really sparked as a student. In 1996, while studying winemaking at the University of Adelaide, I was fortunate enough to receive a Summer Studentship with the Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture. The project I undertook had been conceived by Garry Crittenden, a pioneer of Italian grape varieties in Australia. He was looking for some hard data and I guess a scientific basis to the work he was doing to introduce these varietals to the industry and wine-lovers alike.

Thirty years ago, hardly anyone in Australia wanted to be drinking nebbiolo or arneis. They probably hadn’t even heard of those varieties. In our research, we ended up focusing on Barbera, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Vernaccia di San Gimignano, Dolcetto and Arneis. Garry brought alongside viticulturist Dr. Peter Dry and Dr. Jim Hardie, the Director of the Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture, to direct the project.

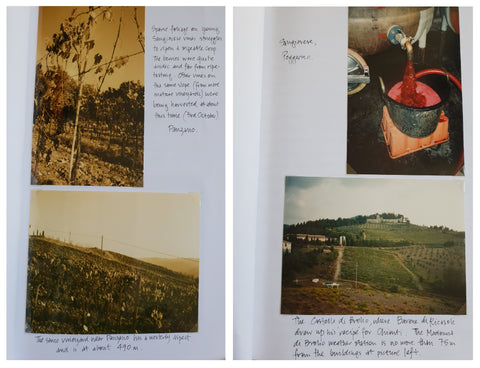

Really getting immersed in that project, delving into the technical view and learning about the qualitative inputs to growing these grapes, just opened up a new world for me. Mind you, I was still quite green, having only done a year of winemaking studies. I started corresponding with universities and producers in Italy and looking for climatic data sets and production details, zeroing in on Barolo and the Langhe, but also Tuscany, especially Chianti. Correspondence was mainly by fax machine! The project sponsored me to visit these places in September 1997, and I had a wonderful opportunity to meet key producers and researchers. Originally the aim was to produce a short article for the Grapegrower and Winemaker magazine. But after a while, I’d produced so much work and was quite passionate about the subject, so Garry said, there’s too much information here, let’s do a book.

Really getting immersed in that project, delving into the technical view and learning about the qualitative inputs to growing these grapes, just opened up a new world for me. Mind you, I was still quite green, having only done a year of winemaking studies. I started corresponding with universities and producers in Italy and looking for climatic data sets and production details, zeroing in on Barolo and the Langhe, but also Tuscany, especially Chianti. Correspondence was mainly by fax machine! The project sponsored me to visit these places in September 1997, and I had a wonderful opportunity to meet key producers and researchers. Originally the aim was to produce a short article for the Grapegrower and Winemaker magazine. But after a while, I’d produced so much work and was quite passionate about the subject, so Garry said, there’s too much information here, let’s do a book.

Vintage in Barolo

After the book was published, and I’d graduated, I felt I had to do a vintage in Italy. I actually ended up going there twice, and working there really grounded all the research I’d done in a practical and emotional way. Learning in more detail how the varieties were grown and made into wine, how they married up with local cuisine, learning the often very different ways of going about winemaking in Italy, sparked new ideas for me.

The Italian palate for food and wine is different, quite different, for example, to the French palate or the American palate, if you can generalise that broadly. That’s why they’ve chosen those varieties over two millenia. I found myself constantly asking, why is this variety grown here, why does it have so much currency compared to what else is grown here, and so on.

I worked in Barolo for the Ceretto family, who are based around Alba. Because of the labelling regulations in that area, if you have Barbaresco on the bottle you have to make sure the wine is made in Barbaresco. So Ceretto had four or five wineries based all around the Langhe. They had their main winery based in Alba, a little winery up in Castiglione Falletto, another one in Barbaresco, a distillery in La Morra and a Moscato winery in the Asti area. On any given day we’d be based at one of those places doing typical vintage work.

Moving around so much and seeing the region and its food changed the way I thought about winemaking. The menu is very seasonal. You would walk into any restaurant and they’d all have the same dishes, and there was a totally ingrained understanding that a dolcetto goes with this dish, a Moscato with that, and so on. Often the food can be quite bitter – Italians love things like radicchio, Campari, aperol, and you can find that reflected in the wines. It’s a textural and phenolic thing, with just a twist of bitterness.

The varieties I was looking at are naturally more tannic, less fleshy, less sweet, and more structured. Almost all the Italian varieties are like that, as opposed to, say, the French varieties. They are not necessarily high acid, but they are more textural, more phenolic, and more savoury.

What I also found interesting were the totally different approaches to winemaking. They didn’t use inert gas as is common here, in fact they would get more air into the whole winemaking process. They would press the wines harder and revel in the bitterness of some of the grape varieties.

The viticulture is amazing, it’s impressive the amount of handwork involved in manicuring the vineyard, in yield reduction, in getting the vines in balance. Whereas in Australia there are very few vineyards that operate like that because the labour costs are higher and the price achieved in the market is lower.

Back in Canberra

Barolo has a very unique climate. It’s a continental climate which means that it’s essentially very cold in winter and gets quite warm in summer, it’s not moderated by the seas. And so it’s technically quite a warm little area even though it’s close to the Alps. It has a shorter growing season than more maritime areas and there’s a prevailing humidity from late summer into autumn, and that natural humidity helps to tone down the aggressiveness in the tannins.

For that reason I was thinking nebbiolo would be a bit of stretch in a dry hinterland climate like Canberra. The wines would look pretty tough because we don’t have that humidity. I was much more interested in the prospect of sangiovese because the climate is a little bit closer to the climate in Tuscany. We’re not as maritime as Tuscany but we have a more similar temperature summation and rainfall distribution.

I thought Beechworth and Canberra were particularly well suited to sangiovese based on the data that I’d examined in our book. In fact, Bryan Martin, a pioneer of sangiovese in the Canberra District, tells the story that the reason he planted sangiovese here was that he read the book!

In the early days of the Collector label, I was fortunate enough to work with some fantastic growers in the region who were ready to push the boundaries.

Wayne and Jennie Fischer, who I was working with quite closely (and still do to this day) were looking at grafting over some vines in 2008. I suggested sangiovese to them, and based on my research, I also suggested a mix of sangiovese clones, as well as canaiolo nero, mammolo, colorino, and malavasia nera. I’d tasted these varieties when I’d visited producers in Chianti during my research, and was intrigued by the layers of complexity they brought to the wines.

I was also working with two other vineyards in the region to introduce a mix of sangiovese clones. I was keen to get sangiovese on a few different sites and spread across different soil types in the region.

I renovated another vineyard, partially planted to sangiovese, and grafted the rest of it to sangiovese. It had originally been set up according to the orthodoxy at the time, with 1.5m vine spacing, a fairly high cordon height which didn’t allow much room to train out the foliage on the vines, and which had been under-invigorated for some time. I essentially chopped it back, retrained it, lowered the cordon height and fruiting wires so that we had more room to train up the foliage. This meant we could get a bigger canopy for the grapes to ripen. I moved to cane pruning and arched canes, so that we could get even budburst and even shoot growth, to ensure everything ripened uniformly and optimally.

At the end of all this we had a mix of sangiovese clones, and small quantities of traditional Chianti varieties, that were planted in the region on a range of sites on the two main soil types of the region – red loam over shale, and granite. The breadth of the resource is quite important to us.

Winemaking

My vision has always been for a wine that is faithful to the sangiovese variety. For a while, a lot of sangiovese hitting the market was a shandy of sangiovese and merlot, cabernet or shiraz in that Super Tuscan mould. These can be beautiful wines, and indeed there are beautiful Tuscan cabernets and so-called Super Tuscans that are absolutely world-class.

But to me the more compelling sangiovese wines are really sangiovese driven and a pure expression of that variety.

The first proper vintage of our Rose Red City sangiovese was in 2012.

I destem and crush the bunches. The variety doesn’t support a lot of stalk inclusion, it makes the wine look a bit hard and green edged. We vinify each block and clone separately, and the other Italian varieties like the mammolo, canaiolo nero, etc, are also fermented separately.

Sangiovese can be quite a reductive variety and it needs some air through the winemaking process, it needs to be racked. It’s also important not to over oak it.

It’s a challenge to make a generous wine from sangiovese, and that comes back to the viticulture. Sangiovese can be naturally high yielding, so vineyard management is critical. This comes back to the importance of hand work in the vines. We manage these vineyards organically – although we are not certified – and this comes with its own costs in terms of time and labour. But what is more important to me is that the vines are in balance. You have to stay on your toes for the whole growing season, ready to respond to the vagaries of the weather, and time your interventions accordingly. I know you can taste the difference in the wine.

In Canberra, we’re growing sangiovese at the cool margin. It’s one of the last varieties we harvest, along with canaiolo, colorino and mammolo. Generally, varieties that are grown close to their cool margin are really good examples of that grape, because they have a longer time to ripen and develop flavours and aromas. It’s when they ripen in the cooler part of the season that you can get that more nuanced expression of aromas and flavours.

In Canberra we get a medium weighted, elegant expression of sangiovese. There’s a brightness and zing, and the characteristic fresh cherries of the variety. The palate has firmish tannins and peach-kernel succulence!

The Rose Red City

The Rose Red City is not necessarily for early consumption, it is made for the long haul. As a variety, unless it’s made in a particular way, sangiovese does take a little while to settle down in bottle and really blossom. I expect our wines to start looking approachable from two years in bottle and onwards.

I love the structure and the moreishness of it. The fact that you can’t really get bored with it. It’s not cloying or overbearing. That’s why it is universal currency.

It has a noticeably very structured and tight palate, with fine grained tannins that encourage you to have another sip.

It sits so well with food. That’s the style. For me, it goes really well with protein dishes, like a T-bone, ragù, meatballs. The structure of the wine helps cut through oily vegetarian dishes. Its savouriness complements most kinds of chargrill. It matches well with heavy sugos and high acid tomato based dishes. A classic pairing is sangiovese with a tomato-based pizza. You can’t get much better than that.

I would age good vintages of this wine for fifteen to twenty years. There is now about twenty years of history of the variety in the Canberra region and some of the wines that were made then are very fresh and still improving.

I believe sangiovese is going to continue to develop towards the mainstream and be a staple of wine consumption in Australia. There will be continuing refinement in terms of grape growing and winemaking, elegant expressions of sangiovese, and some thoughtful blends. It’s a variety that continues to throw up challenges across the country and as the winemaking community learns more about it, we can expect its pedigree will continue to build.

For more on our current release, the 2017 vintage, click here.